In the final part of the Money: A Prolegomena series, we look into the last key macroeconomic concepts explaining some of the dynamics of money. We then venture into the debate between chartalism and metallism. We conclude with a brief summary of the entire series.

Flux and Reflux

Payment/Initial Financing vs Funding/Final Financing

If the Hierarchy of Money and the Four Prices of Money describe the structure of the system, then flux and reflux describe its dynamics. In any monetary system, the movement of money unfolds through a dynamic interplay between initial financing and final financing as Auguste Graziani termed them. Perry Mehrling refers to these processes as payment and funding.

Initial financing (flux) is the creation of purchasing power—it involves the issuance of IOUs that expand the money circuit. This is when credit is created and injected into the economy via the creation of new markets. Funding (reflux), by contrast, is the process of extinguishing those IOUs, either through repayment or through conversion into higher-quality IOUs, such as money. Flux expands; reflux contracts.

This logic applies to both public and private finance. In public finance, initial financing occurs when the state spends money into existence—creating purchasing power through expenditure. Funding, in this context, involves withdrawing money through taxation. The state first spends, then funds—expenditure precedes revenue.

But note: one actor’s initial financing can be another’s funding. Your purchase of equity was flux from your perspective, but for the firm issuing the equity, it was reflux—they were funded. With that funding, the firm could invest in clean technology, generate profit, and allow the cycle to continue.

In circuit theory, initial financing specifically means the beginning of a circuit. Final financing naturally entails the end of a circuit. The circuit is basically the history of a particular denomination of money from conception to its destruction. Circuits form the backbone of the economy, mapping the flows of money that sustain economic activity..

Consequently, it's crucial distinguishing between the objective perspective of circuit theory and the relativistic perspective of monetary realism. These aren't contradictory positions, but rather different analytical models for studying the exact same phenomena. Circuit theory is best for analysing how monetary flows influence and shape economic activity. Monetary realism is best for analysing individual transactions and whether from an agents perspective whether they are engaging in flux or reflux.

Elasticity vs Discipline

If flux and reflux describe the motion of money—its expansion and contraction—then elasticity and discipline describe the forces that shape that motion. They are the underlying tendencies that push a monetary system toward either greater creation (flux) or greater settlement (reflux).

Elasticity is the system’s capacity to expand credit and purchasing power when needed. It reflects a willingness to create IOUs and accommodate new spending. When elasticity is too low, credit is scarce, demand is suppressed, and the economy suffers under the weight of its own inertia. But too much elasticity, and the system becomes dangerously loose: credit grows beyond the productive capacity of the economy, leading to inflationary pressures or the mispricing of risk—what Hyman Minsky called financial fragility. Central banks typically impose discipline by raising interest rates, making credit creation more costly.

Discipline, by contrast, is the system’s ability to enforce repayment, to compel reflux. It ensures that IOUs are not only created, but honoured. When discipline is excessive, it suppresses economic activity, favouring deleveraging over investment. This is the terrain of debt deflation, where efforts to repay debts contract the money supply faster than debt itself is reduced. There is too little liquidity in the system. Central banks typically 'loosen' monetary policy by making it easier for private sector agents to lend creating elasticity in the system.

Elasticity and discipline are very much like yin and yang within the monetary system. One expands, the other constrains. One fuels growth, the other preserves solvency. Markets oscillate between the two, and a stable monetary system must strike a balance between them. When either force dominates for too long, the result is instability—boom, bust, or both in sequence.

Understanding elasticity and discipline as systemic forces reveals that monetary stability is not about targeting a fixed supply of money. It’s about managing a dynamic, evolving hierarchy of promises—ensuring the right balance of creation and redemption, optimism and caution, flux and reflux.

These dynamics explain how money expands and contracts in practice. But to fully grasp money’s place in society, we must ask a deeper question: what gives money value in the first place? This takes us to the long-standing debate between Chartalism and Metallism.

The Great Debate

Chartalism vs Metallism

The historical debate between Chartalism and Metallism lies at the heart of our understanding of money’s nature—whether it derives value from the state or from commodities.

Metallism holds that the value of money is derived from its link to a commodity, typically gold or silver. Under a gold standard, for example, money is pegged to a specific quantity of gold; under a silver standard, to silver. For most of history, societies operated with commodity money: sometimes directly—as with shells, salt, or minted gold coins—or indirectly, by pegging their currency’s value to a metallic anchor.

Chartalism, by contrast, asserts that the value of money stems from the sovereign’s authority. A state gives its currency value by demanding taxes be paid in it, creating demand for the currency. Legal tender laws reinforce this by compelling its use in settling debts. Moreover, the sovereign decides which commodity, if any, shall serve as monetary backing—and at what rate. Even under metallic regimes, it is the state that declares which metal holds primacy and sets its exchange ratio.

Today, Metallism is empirically false. No modern economy backs its currency with gold or silver. All major currencies are fiat—backed not by metal, but by trust in the authority that issues them, typically the central bank and treasury.

Does this mean Chartalism is true? Not entirely. While modern systems are Chartalist in structure, most money is not created by the state, but by private banks—upwards of 96% of the money supply. Banks extend credit by issuing deposits, denominated in the sovereign’s currency and exchangeable at par. Their capacity to do so, however, is licensed and regulated by the state.

As Perry Mehrling aptly argues, the system is hybrid. It is neither wholly Chartalist nor Metallist, neither purely public nor purely private. It reflects a monetary duality, in which the sovereign sets the rules of the game while private actors generate most of the plays. We live in a fiat-chartalist regime, but one layered with privately created money operating under market incentives.

In the hierarchy of money, the sovereign's currency remains supreme. This is evident through phenomena like Gresham’s Law: in a system of multiple forms of money, “bad” (or lesser) money drives out “good” money in circulation. Bank deposits are not equal to physical currency in safety or liquidity. If all depositors demanded cash simultaneously, the system would falter. This reveals that state-backed currency is the ultimate domestic settlement asset.

Nonetheless, the central bank, while powerful, is not omnipotent. It nudges rather than commands. Its primary tool is interest rate policy, through which it influences—rather than dictates—the elasticity and discipline of private money creation. The central bank uses monetary policy as a means of influencing the forces of elasticity and discipline keeping them in balance. Yet markets influence central banks as much as central banks influence markets. The relationship is dialectical.

Chartalism certainly describes key facets of today's modern monetary systems. Governments determine what is legal tender and imposes taxes on the populace. However, on top of that is a vast layer of privately issued money with a life of its own.

This brings us to the yin and yang at the heart of monetary governance: a public-private hybridity. Both the state and the market play constitutive roles. The boundary between them is not fixed, but negotiated and dynamic. Sometimes markets overpower the state—such as in financial bubbles or capital outflows. At other times, the state imposes its will—such as during wartime finance or crisis bailouts. Where one sees liberty, another sees instability; where one sees authority, another sees repression.

A historical example makes this concrete. As Allyn Young observed in his essays The Mystery of Money and The Monetary System of the United States, America’s monetary history is a study in the tension between state decree and market reaction.

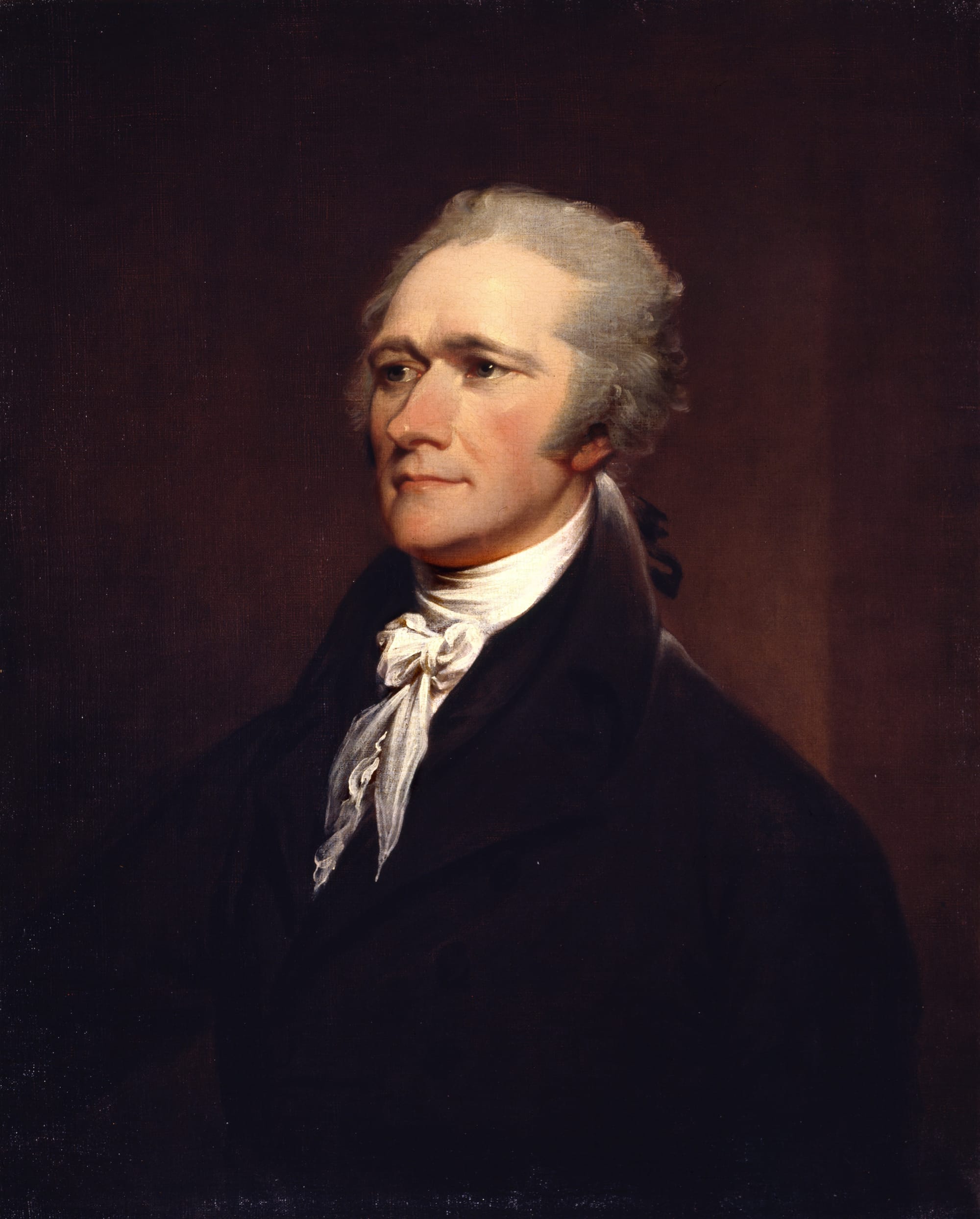

In 1792, President George Washington signed the Coinage Act, authored by Alexander Hamilton, which established the U.S. Mint and formalised the dollar as the nation's currency. The Act created a bimetallic standard, fixing the ratio of silver to gold at 15:1 and pegging the dollar to the Spanish silver dollar. Coins were issued in copper, silver, and gold—valued by the state and minted by public authority.

Yet the market undermined the system almost immediately. Gold’s market value shifted, moving the true ratio closer to 15.5:1. As a result, gold was undervalued and vanished from circulation, while silver flooded the system. Subsequent legislation adjusted the ratio to 16:1, eventually phasing out silver for large payments. By 1853, silver was legal tender only for small transactions.

As Allyn Young notes, the silver standard was an endorsement of cheap money. Creditors favoured gold-backed money because the value of debts rose, whereas debtors preferred the cheap money of the silver standard.

The episode reveals a core lesson: sovereign authority can decree, but it cannot dictate market behaviour. Even with legal power, the state found its coinage policy misaligned with market prices, leading to practical failure. Despite the intent of the 1792 Act, the U.S. never had a robust gold currency in circulation—until later acts recalibrated the system.

The broader insight is that economic liberty constrains state power, just as state authority limits market excess. Sovereignty is not absolute. The state can shape conditions, but it cannot escape the consequences of those conditions. Monetary regimes, like societies themselves, engage in a fragile dialectic—a constant negotiation between order and freedom.

Thus, in choosing a monetary system, we are not merely selecting a technical apparatus—we are deciding the balance of power between public and private forces, between state and citizen, between decree, demand, and liberty. Economic liberty constrains the state's authority empowering market forces, however the constraints imposed still give the state liberty in influencing the market. When states decree what the nature of their monetary regime is, it has a direct impact on how free citizens are in that's states economy. More control is not necessarily good, for instance debtors didn't benefit from the moves towards gold. Meanwhile, unfettered markets and private desire destabilise the system emphasising private interests over the common good.

This balance cannot be established through force of will. Radical action, if it is to be wise, must arise through the subtle transformation of the roots of imbalance, allowing a new harmony to emerge of its own accord. Unwise radicalism merely deepens disorder, addressing symptoms while leaving the causes untouched. This is precisely why we must understand money.

The constancy of the course lies in doing nothing

yet leave nothing undone [無為而無不為]

If lords and kings could hold fast to it,

all things would transform of their own accord

- Laozi in the Daodejing §37

As Laozi suggests, balance is not imposed but cultivated. With that lesson in mind, we can draw together the strands of this prolegomena.

Conclusion

We now have a conceptual apparatus for building a political economy which has money, both its impact for good and ill, at the centre of it. Money is ultimately a social technology which facilitates both production, the organisation of society, and the building of networks beyond the polity. Its creation by private banks and the state is integral for both creating markets but also enabling financial instability that can destabilise the entire economy.

We can see that money creation via credit expansion through the payment of interest places a systemic trajectory toward growth, especially exponential growth. However, we should not reduce the civilisational destruction of the biosphere squarely on interest alone.

The overall monetary system is not one born from rational calculation of pursuing self-interest in which money only plays a facilitating role. The monetary system is dynamic and helps shape the nature of the economy. To speak as an economist, money is not neutral. Furthermore, money and power are interlinked. The social technology is used by certain social groups and classes as a means for organising society which helps empower certain groups over others. Money and politics cannot be divorced from one another like we see in neoclassical economics.

This prolegomena gives us a strong conceptual basis rooted in the post-Keynesian, circuitist, and Money View traditions of monetary economics. However, the intellectual and philosophical influences go well past those schools. Daoist dialectics have been encompassed as a novel calculus for thinking about the dynamics of monetary forces and institutions. Anthropology and Marxian materialist theory underpins the critical introduction as well, even if subtle. Influences from Georgism, institutional political economy and classical political economy are also apparent.

There is a rich blend of influences from numerous traditions which will be incorporated further after an introduction into Biophysical Economics is complete. The mission of Material Reason is to build a strong intellectual pillar for the left—one rooted in political philosophy, political economy, and the natural and social sciences—on which future strategies and institutions can stand.

Bibliography

Fauvelle, M. (2024) Shell Money: A Comparative Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Elements in Ancient and Pre-modern Economies).

Graziani, A. 1990. The Monetary Theory of Production. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Laozi. Trans: Ziporyn, B. 2024. Daodejing. New York: Liveright

Mcleay, M., Radia A., and Thomas, R. 2014. Money in the modern economy: an introduction. Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1. Bank of England

Mcleay, M., Radia A., and Thomas, R. 2014. Money creation in the modern economy. Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1. Bank of England

Mehrling, P. Economics of Money and Banking. Coursera

Mehrling, P. 2012. The Inherent Hierarchy of Money. Source: https://sites.bu.edu/perry/files/2019/04/Mehrling_P_FESeminar_Sp12-02.pdf

Young, A. Mehrling, P.G., & Sandilands, R.J. (Eds.). (1999). Money and Growth: Selected Papers of Allyn Abbott Young (1st ed.). Routledge.